Credit card debt can be very expensive. But if you're paying only the minimum when you can afford to do more, it could be that your past is to blame.

When you carry a balance on one or more cards from month to month, you wind up paying far more for the items charged as interest stacks up, and wiping out that balance can take decades.

But paying off a credit card isn’t always a simple task. While it’s important to understand how the interest on such debt works against you, managing credit card debt isn't always a case of "if you know better, you’ll do better." For those of us with a history of long-term financial hardship, this is especially true.

My own financial track record proves this. Despite understanding how carrying credit card debt could hurt me, I didn’t make a significant effort to pay it off. First, because poverty didn’t allow it, but later because old patterns are simply hard to change.

Understanding the true cost of credit card debt can provide an added incentive to "do better," but taking action requires means and, in some cases, shedding years of faulty thinking and emotional attachment to money. First, let’s talk about that incentive.

Understanding the high cost of credit card debt

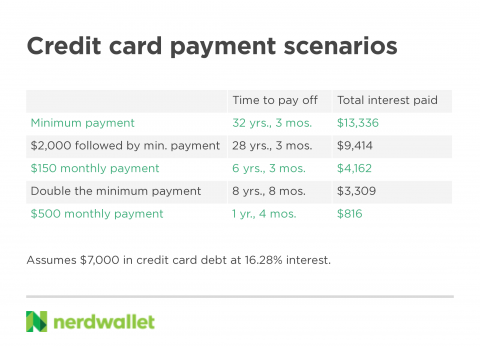

If you carry about $7,000 in credit card debt and make the minimum payment only, it will take over 32 years to pay it off and cost $13,300 in total interest. While $7,000 in credit card debt may seem like a lot to folks who pay their balances each month, NerdWallet’s 2021 Credit Card Debt Study found this is approximately how much people who carry revolving credit card debt owe, on average.

The minimum payment is just that: the smallest amount you can get away with paying without running into trouble with your credit card issuer. Doing more than the minimum — even by just a little bit — can have a major impact on the cost of your debt.

For example, if you receive a $2,000 income tax refund this year and use it to get a jump-start on a credit card balance, moving back to minimum payments after that, you’ll shave about four years and $4,000 off the debt payoff.

If you double the minimum payment each month, it will take about eight and a half years to pay off the balance, and cost $3,300 in interest, a full $10,000 less than making the minimum only.

Take action

If you’re able, formulate a plan to get your credit card debt paid off by paying more than the minimum payments. You’ll also need to either stop charging more or resolve to pay off each month’s new purchases on top of your overall debt payment. A combination of making a budget, finding ways to save on expenses and boosting your income with a side gig can be very powerful.

The debt snowball method is one empowering strategy. You pay off credit balances from the smallest to the largest, which gives some quick signs of progress. Don’t close cards as you zero out the balance, though. The only thing better than having a stash of cash in your emergency savings is having that cash and access to your lines of credit.

Now that we have the math out of the way, let’s talk about what could be standing in the way of you paying off your debt.

Barrier No. 1: Money

Saving all of this money on interest assumes you can make more than the minimum payment. And sometimes, that’s just not possible. As of 2019, 34 million Americans were living in poverty, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Within the past year, many more were affected by the pandemic — facing job loss, reduced hours or hefty medical bills — and fallout from natural disasters, all of which can make it difficult to pay the bills.

Take action

If you can’t pay more than the minimum, pay the minimum and focus on more pressing concerns such as keeping the lights on. If minimum payments aren’t even possible, contact your credit card company to inquire about hardship programs or consider getting into a debt management program. Don’t be afraid to look into bankruptcy, which wipes out truly overwhelming debt so you can get a fresh start.

Barrier No. 2: Your mindset

Having cash on hand or in an easily accessible savings account can feel better than putting it toward debt that feels intangible and ever-present. After all, what if you have a money emergency and need that cash? The electric company and landlord might not accept credit cards.

This line of reasoning can arise from years of financial insecurity. It was my attitude toward credit card debt for a long time. I wasn't a money "Nerd" from the get-go — I grew up in the lower-middle class and started early adulthood as a single parent in public housing receiving government assistance. What changed? First, I developed the means to pay more than the minimum on my debt, through a combination of hard work, luck and privilege. But it took much longer for me to fix my relationship with credit.

Living in poverty shapes how you use and think about money. When money is tight, there are only so many levers within your control, and each choice you make is a precarious one. For someone living in poverty or even close to it, a credit card is a luxury and a safety net, a stand-in for a cash emergency fund. A few particularly tight months — maybe due to higher utility bills during a cold snap or unexpected auto repairs — can seed a seemingly insurmountable debt. As that debt grows and your income doesn't, your outlook seems more and more hopeless. Your safety net becomes a prison.

Even once your financial situation begins to change, steering those financial coping mechanisms and attitudes you have about money in a new direction takes time and considerable effort. I resented paying more than the minimum on my debts but eventually, begrudgingly did it anyway, because I saw the math and knew it was good for me. I battled feelings of dread when it came time to pay my bills each month, long after I had stopped worrying about the lights getting shut off because for so long, money management was connected to overwhelmingly negative feelings and outcomes.

Assuming readers will see the light and make the better choice simply because the math makes sense is shortsighted. It fails to acknowledge the complex personal history that plays into every individual’s financial choices. So here is that acknowledgment: Money is far more than the paper it's printed on or the things you can exchange it for. For many of us, money — or more accurately the absence of money — is directly tied to feelings of fear, insecurity and even a lack of personal worth.

Take action

When you live paycheck to paycheck, you use credit differently than when you live in relative financial comfort. For the financially insecure, credit is a stand-in for a true emergency fund; for people with means, it’s a tool to earn rewards and qualify for better rates on home and auto loans, for example.

Learning how best to manage credit card bills is good knowledge, no matter your current situation. But as your financial situation changes — maybe you learn a new trade or get a promotion — work on changing your relationship with money, too. This change might be filled with setbacks and it may take years. But working toward a healthy relationship with credit pays off, in more ways than one.