Many or all of the products featured here are from our partners who compensate us. This influences which products we write about and where and how the product appears on a page. However, this does not influence our evaluations. Our opinions are our own. Here is a list of our partners and here's how we make money.

Welcome to NerdWallet's Smart Money podcast, where we answer your real-world money questions.

This week's episode is dedicated to a conversation with journalist Kimberly Atkins Stohr. We discuss her series about how to solve the racial wealth gap.

Check out this episode on either of these platforms:

Our take

The racial wealth gap between Black and white Americans began with the institution of slavery, and it has been reinforced throughout history by discriminatory policies, such as redlining. These practices made building wealth difficult for many Black Americans. The median wealth of a white family was roughly $188,000 in 2019, according to the Brookings Institution. For Black families, that number was just over $24,000. Solving the racial wealth gap will take a reimagining of how our financial system works, including the structure and use of credit scoring, says Kimberly Atkins Stohr, senior opinion writer and columnist for Boston Globe Opinion.

When it comes to credit scoring, Atkins argues that the structure of credit scores is discriminatory and leads to disparities in scores between Black and white Americans. For example, mortgage payments are counted as good behavior, while rent payments are generally not considered. Since Black Americans are less likely to be homeowners than white Americans, they can have fewer opportunities to build up good credit.

Opt-in tools like Experian Boost and UltraFICO can help mitigate the financial challenges Black Americans face. But Atkins suggests curbing the practice of using credit scores for non-credit related decision-making, like whether or not to hire someone. Solving the racial wealth gap will need to be approached on numerous fronts, and it starts with reimagining the systems we currently have in place.

More about the racial wealth gap on NerdWallet:

Have a money question? Text or call us at 901-730-6373. Or you can email us at [email protected]. To hear previous episodes, go to the podcast homepage.

Episode transcript

Sean Pyles: The racial wealth gap has been carved over centuries. Can it be bridged in our lifetime? Welcome to the NerdWallet Smart Money Podcast. I'm Sean Pyles.

Liz Weston: And I'm Liz Weston. In this episode, we're talking with Kimberly Atkins Stohr, opinion writer for The Boston Globe and the inaugural columnist for The Emancipator. The Emancipator was the very first anti-slavery newspaper in the United States when it was founded over 200 years ago. Today, it's been given new life as a collaboration between The Boston Globe and Boston University's Center for Antiracist Research.

Sean Pyles: Kimberly recently wrote a series for The Emancipator about solving the racial wealth gap, including how we got to where we are today, the prejudices built into credit scores and the challenges that Black Americans face when it comes to student debt. Welcome to Smart Money, Kimberly.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: Thank you so much for having me.

Sean Pyles: It's great to talk with you. And the racial wealth gap can seem like this static, unchangeable reality in our society, which is why I really appreciate the forward-looking, actionable tone of your piece titled, "We can solve the racial wealth gap." But the problem is really significant. For example, one statistic that you point out is that the median wealth of a Black family in 2019 was $24,000, while for a white family, it was $188,000, which is a huge disparity.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: Yes. And one reason that we wanted to look at this in this forward-looking way, as you mentioned, is that it really is in the tradition of abolitionist newspapers, like the original Emancipator and others. If you go back and read them, they didn't just advocate for the end of slavery; they envisioned what society could look like if Black people were fully equal participating citizens. And that's the approach that I took here. It's not just identifying a problem, showing it with statistics, or talking about how we get here. But saying, "Hey, how can we remove some of these barriers from these systems so that the playing field can be at least more equal than it is today?" It's really solutions-focused.

Sean Pyles: And you talk a lot about reimagining the way that our current structures are designed because they are all made up by different people at different points in time, and we could change them if we had the will and the momentum to do so. But I want to take a step back and dig into some of the history behind the racial wealth gap that we are facing today. We know that the enslavement of a number of Black people was a big cause for this, but can you talk about some of the other issues that led to where we are today?

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: Yes. Well, that's really where it began with the institution of slavery. Of course, after that, it was very difficult, often illegal, for enslaved people or formerly enslaved people to own property — that was by design. But even when some of those barriers were technically lifted, you had redlining and other Jim Crow laws that were put in place that made property ownership out of reach for a lot of Black Americans. And we, of course, know that property ownership is the cornerstone of wealth building. It's what you pass on to your families. It's most people's biggest investment. And to this day, the rate of homeownership for Black Americans is much, much lower than for others, so that's really the biggest part of it. There are also other factors like employment discrimination, but really land ownership is the crux of it.

Sean Pyles: And you also write about how the racial wealth gap costs all of us. Can you describe what you mean by that?

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: Yes. I saw this statistic, and it really was one of the reasons why I wanted to do this series and sort of incentivize everyone to think about this as not just a problem for Black people but a problem for all people. When you look at the wealth gap and the way that it impacts Black Americans' buying power, Black Americans' ability to participate in the economy — to grow the economy, to open businesses, to create jobs — in the last 30 years, it has sapped $51 trillion from the gross national product.

Sean Pyles: It's a massive amount of money.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: That is a lot of money. That's a lot of money. That's costing everyone, from the people who are paying for groceries to Wall Street investors. So I think if I could craft it that way and make everybody say, "Huh, there's money to be made here, not just for Black people, but for everyone." Then maybe everyone will be more interested in trying to find solutions to the wealth gap.

Liz Weston: And Kimberly, you've mentioned a few specific areas of the financial system that need to be improved to help close this gap. Can we start by talking about credit scores? Because that's my area of interest. So can you describe the current disparities around credit scores and how they came to be?

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: So I wanted to look at credit scoring, mostly because it's so opaque and I still don't understand exactly what that number means and what it's all about. And I thought if I can explain that, maybe I can understand why there is a racial gap there as well. But it turns out when I looked into it, it isn't so much in the way the scoring is done; it's the way the scoring is used. So we know that credit scores are used for things like obtaining loans, and that seems to make sense. You want to have some sort of gauge about someone's creditworthiness before you lend to them. But it's also used in so many other ways. It's used for job applications when there is absolutely no correlation between one's credit and their ability or suitability for a job.

Liz Weston: People are having their credit histories held against them when there's absolutely no reason and no proof that there's any relationship between credit and people's performance on the job.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: It's also used for obtaining things like utility, just to heat your home and to get electricity in your home — basic things that everybody should have access to. So that's one problem, but another problem is the factors that go into a credit score or a credit report. The biggest example, we're getting back to land ownership. Mortgages — when somebody has a mortgage and they pay it regularly — are a huge, huge, positive booster of one's credit. But at the same time, rent payments are usually not counted. Well, there is a much bigger percentage of Black people in America who rent than who own compared to white people. So that in itself is causing a disparity in the credit scoring when you don't have that history counted.

And really, when you don't have a mortgage and you have a lack of the kind of traditional loans, like a mortgage or a personal loan or a business loan, a lack of that counts against you in your credit score. And it's a lot of other factors that go into it that really mean that although credit scoring is supposed to be blind, it's supposed to be objective. In actuality, it really isn't.

Sean Pyles: One thing this reminds me of is this book I read called "Algorithms of Oppression." And it talks about how we can sometimes think about these models like credit scores and even search algorithms as being neutral in a way, when in fact, they carry the biases of the people who designed them.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: That's absolutely right. And I think that's an important way to look at it. I think sometimes, when we talk about systemic racism in this country, people think about people purposely saying, "Okay, we're going to put this policy into place to hurt Black people." And that has happened throughout our history. But I think one way that it's perpetuated so often now is that you have systems in place that have seemingly objective reasons for having them there. Or they are perpetuated by people who have no intention of being racist or discriminating, but by way of design, they naturally do that. And they perpetuate it, even if the people who are carrying them out don't know it. And I think that's the important way to distinguish the way we're talking about this.

Liz Weston: You also mentioned that there can be a certain pride taken in paying cash rather than using credit, and that can actually hurt people in terms of their credit scores. If they're not using credit, they're not getting credit. They're not building up their credit scores.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: That's exactly right. There's a powerful story that was told by Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley from Massachusetts about the difficulty she had coming from a family that was credit invisible, which is another problem. You're not using the credit system. The credit system can't see you, so you don't have a score. You can't build a score. And how in a lot of communities, paying cash is seen as being a virtue — showing that you have the ability to pay for something, but in actuality, it is harming you.

So when people who can't access traditional lines of credit, like mortgages, like personal loans, are steered toward things like payday loans, rent-to-own establishments and other things that have just extortionary interest rates and really, really usurious policies that make them more likely to default and more likely to have negative information reported to their credit score. So it sort of locks them into this dual system, which is really a problem.

Sean Pyles: I think that's a great example of the ripple effects of different forms of racial discrimination and disparities in these various systems. It's not just that someone's rent payment isn't going to factor into their credit score. It's that there are going to be other effects downstream of them, maybe not having access to a bank in their neighborhood. And so they go to a check-cashing place, and then they end up paying more fees for that and they have less money in their bank account overall. And all these things compound to help build up the racial wealth gap that we see today.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: That's absolutely correct. It plays a major role when those things just aren't even accessible to you. And of course, it's generational too. If you come from less generational wealth, you have less to start with, and it's even harder to build up your credit, to build up your net worth. You're more likely to have loans from other things, such as student loans, which I also write about. All of these other things are interconnected and just serve to perpetuate the gap further and further.

Sean Pyles: Well, I want to go back to the idea of reimagining this because that is the crux of your series. How do you think that credit scoring models can be reimagined to be more equitable or fair?

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: So again, I thought I would come out of this, doing the reporting, thinking about making credit reporting agencies be more transparent or use a single formula or something like that. And really, the solution is in how this credit information is used. And the biggest takeaway is that it should not be used in ways that are not predictive of whatever you're trying to measure. And that comes from different forms of employment, having basic utilities in your home and other ways that credit scoring can be used — insurance purposes. So, for example, the greatest example is rent, count rent, make rent a positive factor in credit reporting the same way that mortgages are because it does show someone's ability to pay. In fact, for most people, even people in really strained financial circumstances, the first thing that they tend to make sure they pay is their rent.

They want to keep a roof over their heads, and so they're very likely to be a very good risk when it comes to paying rent, and so you don't want that used against them. And again, even though rent isn't counted positively toward a credit score, a potential landlord absolutely can look at a credit score in order to decide whether to rent to someone. So it's a one-way system. It should go both ways. Those are just a couple of the ideas that are put into the piece that I have that can be a starting point. And, of course, this isn't an exhaustive list, but it's meant to start the conversation and start people rethinking the way that the system is set up, and we will continue to examine even more potential solutions.

Liz Weston: Kimberly, you brought up insurance and that's a really interesting area because there's overwhelming research showing a connection between certain credit information and how likely people are to file claims. We don't know why, we don't know what the causation is, but there's definitely a correlation there. But because we can't explain it, it makes it really questionable why we're using this information for insurance, especially when it has such a disparate impact on people. And I think your research showed that when you have worse credit scores, you're going to have higher costs for insurance, and nobody can explain why that is. So why are we allowing this?

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: Yes, we don't know exactly what it is, but it could simply be that the use of that causes insurance to be more expensive for people; they are charged more for it. But the way that it is carried out, like many other systems — financial and otherwise in America — Black people are treated as more risky than other people, even when they actually are not.

Liz Weston: Anybody who looks into how insurance information is being used would have questions about it because you can wind up paying more for car insurance if you have bad credit than if you caused accidents. And that just doesn't make sense to anybody.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: No, it doesn't. And some states, like Massachusetts, have outlawed the use of credit reporting to obtain things like car insurance. But then what happens is a lot of major insurers often don't insure in Massachusetts. I know that when I used to live there and I couldn't take the insurance that I had when I lived in New York, for example, with me into Massachusetts, because they just decided to pull out because of those policies.

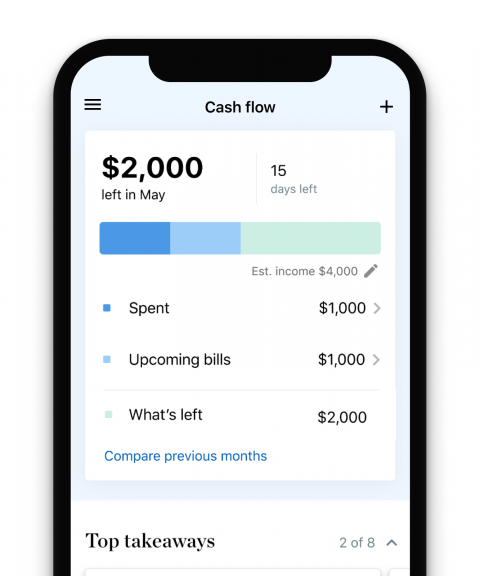

Liz Weston: Well, we know a lot of these problems are bigger than individuals can solve on their own, but we do have some tools that people can use that we wanted to mention. UltraFICO and Experian Boost are services that use information from your bank accounts to help reward good financial habits — like paying utility bills on time, maintaining a cash balance — that typically aren't factored into credit scoring models. So again, we wanted to drop this in as a possible tool for people who want to build their credit and don't have a traditional credit history to fall back on.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: And I want to add one more thing too. There is a proposal by some of the credit reporting agencies to stop using things like medical debt. And that would reduce something like an estimated 70% of medical debt, which of course, you can't control whether you get sick or whether you're in an accident, and that shouldn't be counted as a way to make you less creditworthy. I think that is laudable. In the piece, we call for fully eliminating all medical debt and any other kind of debt that is not predictive of one's ability to pay.

Sean Pyles: Well, now I want to turn to talk about student debt because you have a piece about this as well, and student loans are often seen as "good debt." It's debt that can help people get a degree and maybe land a good job and get on the path toward achieving the mythical American dream. But student loans can actually leave many Black borrowers worse off compared to white borrowers. Can you describe what's happening there?

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: What's happening? It's something that was really personal to me. I don't think I fully understood what the racial wealth gap looked like in real life until I graduated from graduate school, and the amount of debt that I had in my exit interview seemed insurmountable. It was six figures, and it started with a two. And I remember initially just laughing and thinking, "Okay, I just secured a $35,000 a year job and what are they going to do?"

Sean Pyles: You basically had a mortgage of student loan debt.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: Exactly. And so I went to commiserate with my classmates about it. My classmates were mostly white, and none of them had the same issue. Their parents paid for their tuition, and that was the first time it clicked to me that, "Oh, that's generational wealth." My parents would have loved to have paid for my tuition, but they couldn't. So I took out the student loans. My parents, at times, helped me pay those student loans, so that was really just transferring debt to them as opposed to the other way around. And I was a lot farther back in doing things, like buying a home or buying a new car. I bought a used old car that I had to keep getting repaired and I saw my friends advancing in life in a way financially much faster than me. And that's really what made it click. And that happens with Black Americans at a much higher rate than it happens to others.

There was a study that was done called "Jim Crow Debt," which really came to the conclusion that for many, many Black people, student loans are bad debt. They don't pay. There's not the return on investment that you would think when people tell you, 'Stay in school. Go to school. That's the way to be successful.' In many ways, it really is not.

Liz Weston: Black Americans are much more likely to be targeted by for-profit schools. They could be paying more for their education. If they don't finish, then they have all this debt and no degree to help them get ahead. Is that basically what the Jim Crow report was talking about?

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: Well, it's not just for-profit schools. It's really for all levels of education. Black households are much more likely not only to take out student loans, including federal loans. They are more likely to need to take out more or have to supplement those federal loans with private loans that have higher interest rates and don't have some of the protections that federal loans do. Also, even though federal loans are at a lower interest rate, some of them begin capitalizing on your first day of school. So throughout the time that you're going to school, those loans are growing bigger and bigger, which is why I had such a big surprise on graduation day when I finished graduate school. And also, they have the ability to forbear financial hardship. But during those forbearance periods, the interest keeps capitalizing and accruing.

So, it just grows if you can't pay it back. If Black graduates are more likely to have lower wages, once they graduate, from their jobs, then it's even harder to pay back. They have much higher default rates because of that, which, again, negatively affects their credit score. So it creates this vicious cycle that really can make, for a lot of people, student loans a really bad investment.

Sean Pyles: The Biden Administration recently announced measures to cancel student debt. What does student debt cancellation mean for Black Americans with too much student loan debt?

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: It can really make a huge difference. Eliminating student loan debt will sort of set them up to that more even playing field at the beginning of their professional lives or, depending on when it comes, in the middle of their professional lives. In a way that allows them to advance in other aspects of their financial lives, whether it is to buy a house, whether it is to start a business, or become an entrepreneur, in any number of ways. It's also shown that despite a lot of criticism for debt forgiveness saying that it's unfair or it will greatly benefit those who don't need it — your doctors and your lawyers and such who are making plenty of money and don't need that forgiveness — generally people in those fields and people at higher income levels don't have student debt because they've paid them off. They're much more likely to have paid them off and have had the wherewithal to do that.

The people who get trapped are in the lower-income field. So even if there is some windfall for a few people who are wealthier, by and large, it will benefit the people who need it most. Just as student loan debt disproportionately affects Black students, Black borrowers, Black graduates, forgiveness will also go very far in removing the racial wealth gap. But another important point that's a lot of pushback about efforts to think of this as reparations. Student loan debt forgiveness will help everybody, everybody who needs it, regardless of race. So it really is the fastest, clearest solution to not just the racial wealth gap, but just the idea that to get an education should not mean a lifetime, or close to it, of debt.

Liz Weston: The one point that does come up constantly is from people who paid off their debt. They just hate the idea that anyone would get something that they didn't get. And it's like, "You were able to pay off your debt. That's good for you."

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: I agree with that so much. I mean, as I said, I had the debt and I've worked extremely hard for many, many years to pay it off. And that makes me believe in this even more because I wouldn't push that on anybody.

Liz Weston: Thank you.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: And that really shouldn't be necessary. I don't understand that criticism either.

Sean Pyles: A lot of Americans are invested and interested in solving the racial wealth gap but are unsure what they, as individuals, can do. What would be your advice for them?

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: Well, one is to pay attention to your elected officials and what they are doing to address the issue and support people who are doing things to try to address this issue with your vote. There are other ways as well. One thing I looked at — even when it comes to helping more Black businesses secure capital to start and grow their businesses — a model that really revolves around community involvement and community investment is important. Whereas people from their communities can join local advisory boards and really get involved in having a say in what kind of businesses they want in their communities and try to urge lenders to support them. Usually, lenders will look at an application for a business loan in a very dry way and not fully understand what that business can mean to a community.

But if we set up more partnerships where community members are involved in making those decisions and saying, 'Yes, we would love to have this barbershop in our town, or we would love to have this store in our town. It would really serve our community.' And banks understand that can make them look like much better candidates for those loans. So I explore ways to do that too, but I think community involvement and community investment is a key to helping Black businesses and Black people excel.

Sean Pyles: On a day-to-day level, we talk a lot about putting your money where your morals are. And a lot of that can mean shopping at a local Black-owned business, things like that. That does go pretty far and can seem almost a little bit cliche because we've been hearing so much about it for a few years now, but it is nonetheless very impactful.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: It is. It really is. And it's also important to encourage people who have the financial wherewithal, investors, to invest in Black businesses in that same way. It really doesn't take much to support businesses that you want to succeed. Whether you are a consumer, whether you are an investor, it really is incumbent upon people in the private sector as much, maybe even more so, than in the public sector and public officials to do what they can to support businesses and make sure that they thrive.

Sean Pyles: Well. Kimberly, thank you so much for talking with us today.

Kimberly Atkins Stohr: This has been so much fun. Thank you for having me.

Liz Weston: And that's all we have for this episode. Do you have a money question of your own? Turn to the Nerds and call or text us your questions at 901-730-6373, that's 901-730-NERD. You can also email us at [email protected]. Visit nerdwallet.com/podcast for more information on this episode, and remember to follow, rate and review us wherever you're getting this podcast.

Sean Pyles: And here is our brief disclaimer, thoughtfully crafted by NerdWallet's legal team: Your questions are answered by knowledgeable and talented finance writers, but we are not financial or investment advisors. This Nerdy info is provided for general educational and entertainment purposes and may not apply to your specific circumstances.

Liz Weston: And with that said, until next time, turn to the Nerds.